¿FORTUNY WAS SPANISH?

Am I the only one who didn’t know the dazzling Venetian fashion and textile wizard, the Prince of Pleats, the Virtuoso of Velvet, wasn’t even Italian, let alone Venetian? He was born Mariano Fortuny* y Madrazo in 1871, of a long line of artists, curators and collectors in the capital and last stronghold of Spain’s Moorish culture–Granada.

He grew up in Paris surrounded by the works and collections of his ancestors and didn’t even settle in Venice until 1889, and then only because he was allergic to horses, not often encountered in a city dependent on water transport.

1935

Fortuny’s mother, Cecilia de Madrazo, came from a family of artists and two directors of the Prado, who, along with the family fortune, were instrumental in putting the museum on the cultural map.

Fortuny’s mother, Cecilia de Madrazo, came from a family of artists and two directors of the Prado, who, along with the family fortune, were instrumental in putting the museum on the cultural map.

His father, Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, was, according to New York’s Queen Sofia Spanish Institute, “one of the most important artists in the history of Spanish art after Francisco Goya.”

A frequent traveler in Islamic lands, Fortuny y Marsal was fascinated by caftans, turbans, harem pants; he collected the fine fabrics and carpets, rare potteries and metal armor his son grew up surrounded by, in an artistic salon that his mother hosted.

[ ] Ingres, painted by his friend Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz, who was Fortuny’s maternal grandfather and the second in the family to become Prado director. [ ] Arab Before Tapestry by Fortuny’s father, Mariano Fortuny y Marsal. [ ] Fortuny y Madrazo, himself, in silk turban and Berber burnous.

[ ] Ingres, painted by his friend Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz, who was Fortuny’s maternal grandfather and the second in the family to become Prado director. [ ] Arab Before Tapestry by Fortuny’s father, Mariano Fortuny y Marsal. [ ] Fortuny y Madrazo, himself, in silk turban and Berber burnous.

Fortuny’s 1896 Flower Maidens from Parsifal is one of his cycle of 46 Wagnerian mythologies on show in Leipzig to celebrate the composer’s 200th birthday. At the Klinger Forum through July 8 (and possibly Bayreuth thereafter). Palazzo Fortuny, Musei Civici, Venice,

Like much of the cultural elite of his time, Fortuny was besotted with Richard Wagner’s “music dramas” as well as with Wagner’s ideal of the unification of all art forms into a single event. Tapped to work on costumes and scenery for the 1900 La Scala production of “Tristan und Isolde,” he recognized that theatrical lighting failed Wagner’s unified-arts goals. He conducted experiments to find a way for light to flow and change with the texture of the music, that quickly transforms to enhance shifts of mood and atmosphere. He found that light reflected off various surfaces changes such properties as color and intensity, and patented a system to achieve this in 1901. He engineered his next invention, the Fortuny Cyclorama Dome, to allow illusions of a more extensive sky and distant horizon than perspective and stage size could create on their own. “Theatrical scenery will be able to transform itself in tune with music, within the latter’s domain,” he reported. “That is to say in time whereas hitherto it has only been able to develop in space.”

Developed as a stage device, the Fortuny Moda floor lamp has become a residential favorite.

Luxuriously romantic silk hanging lamps, also Fortuny, also still available.

Because a combination of the dome and reflected light meant one stage set could provide several different visual and emotional effects, the costs of scenery could be reduced, along with storage space and the danger of fire.

He applied the dome concept to a collapsible, portable lamp to re-create indoor lighting onstage; originally intended for theatrical use, the hi-tech appearance of the Fortuny Moda floor lamp has made it a lasting icon of residential lighting. He invented the dimmer switch.

All that experience with theatrical costumes and stage curtains, as well as experiments with the effects of light on fabric, fed into the art for which Fortuny is still best known: the figure-skimming, sleek, slinky, sophisticated, glowing, daring, No-Corsets-Need-Apply pleated silk gown, which actually has a patent behind it for the pleating tools as well as for the style. What appears to be ruffling at the neckline and sleeve is not ornament at all but the visible result of lacing front to back with silk cords, which also run through the neckline.

Between the cords and the pleats, the gowns can adapt to a range of sizes. Murano glass beads strung on the cords around the armholes and down the sides–as well as around the shaped hem of the Peplos overblouse–keep the light silk pleats from gaping or ballooning or wandering off with the first stray breeze. The result is both simpler and richer than anything that had gone before. Every element is necessary. Nothing is extraneous. This may well be the first modern garment.

Uncorseted Fortuny.

Corseted S-bend

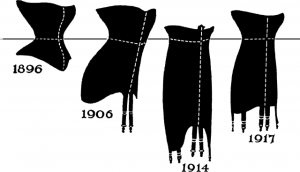

Around the turn of the 20th century, a simpler, more comfortable silhouette began to be discussed, and even showed up here and there in haute couture, but the preferred female profile was still the “S-Bend,” low breasts balanced by a modified bustle, all achieved with specialized corseting and strategic padding. A day dress would be long-sleeved, high-necked, and be worn with a large-brimmed feathered hat pinned to a mass of upswept hair. For evening, it could be sleeveless or short-sleeved, and would have a decidedly low neckline. An over-the top hat may have been appropriate for evening, depending on the event.

Poiret evening gown, 1910, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hobble-skirt 1912 by Cummings, St. Louis

Fortuny was an early advocate of liberating garments, but his contemporary, Paul Poiret, usually gets the credit. Poiret’s styles, however, were fussy and often required corsets to the knee; he also popularized–and may have invented—the hobble skirt. So much for easy movement.

Way off-topic: the 2,500-year-old Charioteer of Delphi has glass eyeballs and copper eyelashes. Delphi Archaeological Museum, Delphi, Greece.

Fortuny, on the other hand, used his patented tools create sharply pleated fine silk that stood on its own as structure and decoration, style and substance. Called the Delphos, the garment was based on the chiton worn by the Charioteer of Delphi, a famous 5th-century-B.C. Greek bronze that had been discovered in 1896.

A chiton was a cloth cylinder made by piecing together a number of woven rectangles, joining them at the shoulders, and holding them in place with a girdle that formed a loosely pleated effect. Fabric was not easily come by in ancient times, so the material had to remain in reusable rectangles.

The Greeks did not cut necklines or armholes into the fabric, but left gaps for the head and arms when they joined front and back at the shoulders. University of Nebraska, Omaha.

Fortuny did the Greeks one better by setting almost permanent knife-edge pleats in his rectangles of fine, light silk–the silk for flow, the pleats for structure.

- Alfred Stieglitz’s 1907 autochrome of his sister, Selma Schubart, in a Fortuny–and a cardigan! (Some think Edward Steichen shot the picture.) Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1955, Metropolitan Museum, NYC.

Fortuny painted his wife Henriette Negrin adjusting the silk cords and Murano beads in her own gown. She named the Delphos and is said to have played a major role in creating it. Note the absence of foundation garments. Museo del Traje, Madrid.

No pattern-making was needed, no cutting, tailoring, dressmaker details, darts, gores, gussets or any of the other slicing-and-dicing techniques typically used to give form to fabric. Even care is easy: simply twist the gown into coils and pop it into a little 9-in-dia box, ready for storage or travel.

1920s MetMuseum.Org

The pleats are virtually permanent, but if a gown should sag a bit at the seat or knees, it would be returned to Venice for a touch-up–no one but Fortuny himself ever knew the secret of the silk pleats, and all efforts to replicate them seem to have failed. Heat and moisture were involved, but how much of each? When did the patented mechanisms come into play? What about chemicals? An assistant recalled having to painstakingly remove a kind of egg glue from the fabric.

Fortuny didn’t consider himself a couturier, didn’t hold fashion shows, didn’t feel obliged to follow trends or chase originality. Over the 40-odd years the Delphos and Peplos were produced, he might nod to the times with higher or lower hems, jewel tones or naturals, a spaghetti strap here, a little shoulder pad there, perhaps some scissor work to create a permanent scoop or V-neck. From the corseted Edwardian Era to the bound-breast Flapper period to Dior’s girdled New Look to the buff-bodied present, the Fortuny gown never went out of style. After he died in 1949, no more gowns were made, yet women lucky enough to find them at auction (up to $20,000) continue to collect them, cherish them, and wear them.

Lauren Hutton in a 1930s Peplos and Coptic cape, shot by Richard Avedon for Vogue.

1940s

Every woman should be issued a Fortuny gown along with her Medicare card.

1910-1920

Sotheby

Knife-sharp silk pleats also make a discreet appearance as insets in the sleeves and sides of his sumptuous printed, painted and stenciled silk-velvet gowns. Once again, silken cords and Murano glass beads coursing down the sides can be used to loosen or tighten the gown to size, while the pleats expand or contract as needed. Fortuny’s velvets are so soft that they follow the body comfortably no matter the number of adjustments.

Top left: loosely adjusted gown.

Top left: loosely adjusted gown.

‘Right: tightly adjusted to hug the figure.

Left: Inset pleats keep sleeve supple.

These velvets reflect their Venetian origins not only in the hues created when the canals mirror changes in the sky, but also in the long history of magnificent textiles produced in the region. From medieval times, Venice was a crossroads of East and West–think Marco Polo–as well as, for several hundred years, the only place self-respecting kings, emperors, cardinals and merchant princes from all over Europe could obtain opulent, innovative velvets with which to intimidate one another.

Venice extended privileges and tax exemptions to innovators, and acknowledged the dyers guild’s critical economic by routinely overlooking such pollution violations as the use of urine as a color fixative. In the 14th century, taking velvet skills from Venice to another city could result in the confiscation of property and a death sentence.

Tintoretto, the Venetian artist known for glowing color and the amazing light and shadow in his treatment of textiles, was the son of a dyer.In fact, Venetian artists from Bellini to Titian, Carpaccio, Georgione, Veronese and Tiepolo were often noted more for the fabric in their paintings than they were for faces, buildings and landscapes.

To this heritage, Fortuny added influences from China, Japan, India, Persia, Turkey, and Northern Africa, Coptic legends and Kufic calligraphies, paleochristian sculptural motifs and Irish manuscript illuminations.

Marcel Proust described Fortuny as “faithfully antique but powerfully original,” and mentioned him at least sixteen times in “Remembrance of Things Past,” where he was the only real character

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

Gift of Mrs. Norbert A Bogdan, 1974. MetMuseum.org

not a fictional composite of several others. Fortuny’s fans have included Isadora Duncan, Gloria Vanderbilt (Anderson Cooper’s mother), Sarah Bernhardt, Peggy Guggenheim, Nijinsky, Lillian Gish, and Orson Welles. And thereby hangs a mystery.

Museo del Traje, Madrid

Some accounts have Fortuny designing the costumes for Welles’ 1952 movie, “Othello.” Others say Welles had the costumes made of Fortuny fabric; doublets have been mentioned, and “three coats.” One tale has Welles bursting in on Fortuny shortly before the designer died in 1949 and modeling some kind of fur-lined item.

Welles himself recalled learning, while preparing to shoot in a small Moroccan city, that his Italian costume–maker was bankrupt. He immediately shifted one scene to a Turkish bath to justify filming male actors naked from the waist up, and hired local tailors to make costumes based on pictures of Renaissance paintings.

In the end, Welles claimed to have had an army clad in armor made of sardine tins, but what of the main characters? Did any of them get to wear Fortuny? Some grainy old black-and-white stills from this black-and-white movie show Welles in a costume that looks as though it conceivably could include this fur-trimmed multi-color coat, left.

Did any Fortuny make it into the film?

Anyone?

*Thanks to Fred Plotkin, master of all things opera, food and Italy, for dissuading me from pronouncing it “FORchinny” and encouraging the use of “ForchOOny”instead.

© Judith Davidsen and jdavidsen.wordpress.com, 2010-2013. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Judith Davidsen and jdavidsen.wordpress.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

1 comment