SHAKER SHOCK

In 1842, Charles Dickens described his encounter with Shakers in this manner: “we walked into a grim room, where several grim hats were hanging on grim pegs, and the time was grimly told by a grim clock, which uttered every tick with a kind of struggle, as if it broke the grim silence reluctantly, and under protest. Ranged against the wall were six or eight stiff high-backed chairs, and they partook so strongly of the general grimness, that one would much rather have sat on the floor than incurred the smallest obligation to any of them.”

Clearly, the man took a wrong turn and ended up at one of the other Utopian communities that thrived in the U.S. at the time. Those simple, celibate Shakers, whose spare, bare wood furniture exerted a huge influence on modern design, were given to wild displays of color. They dyed the cloth they wove salmon, pink, red, Prussian blue, yellow, orange and purple. Almost all original Shaker furniture, built-ins, household objects and even floors were painted colors with names like chrome yellow, red ochre, yellow ochre, red lead, chrome green, Venetian red and Prussian blue. The goal was a neat appearance and efficient cleaning.

To shock visitors into exploring the Shaker use of color, the floor at a 2008 Shaker show at the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts in New York City was painted chrome yellow with red-ochre trim. Over the years, non-Shakers had stripped the paint off most of the furniture, but a yellow washstand is visible at rear, right. Image: Bard Graduate Center.

“People are used to Shaker forms, but not Shaker colors,” says Jean M. Burks, Senior Curator and Director of the Curatorial Department at the Shelburne Museum in Shelburne, VT., who has curated some shockingly colorful shows called Shaker Design: Out of this World. “They tend to think of classic Shaker design as stripped-down brown wood.”

Decades after Dickens’ grim report, non-Shaker, or “worldly,” owners influenced by the Arts & Crafts Movement of the turn of the last century (and another forerunner of modern design) began the practice of stripping Shaker furniture. Today’s Shaker antiques and most museum pieces have been stripped, and even the best copies are unlikely ever to have been colored. Meanwhile, the surviving painted pieces tend to be worn and chipped, which would have horrified their original owners, who are said to have continually refreshed and repainted them.

The Shakers may not have invented the “swallowtailed” oval box, but they made them, used them for all sorts of storage and sold them. They would have kept repainting them to keep them neat and clean. Image: Bard Graduate Center

The Shakers—more correctly the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing—began as dissident English Quakers who left for America in 1774 under the leadership of Mother Ann Lee, who famously once proclaimed, “There is no dirt in Heaven.” They believed cleanliness, neatness and order led to serenity, but they did not believe in drudgery: they hung their famous chairs from wall pegs in order to more easily clean the floors, and hung them upside down in order to keep dust off the seats.

Chairs hung upside down not only to facilitate cleaning but to keep dust off the seats.

Efficiency, neatness and cleanliness only partly account for the pared down nature of Shaker furniture. In 1823, Mother Ann’s followers wrote down the precept, “Anything may, with strict propriety, be called perfect, which perfectly answers the purpose for which it was designed”—73 years before Louis Sullivan’s famous “Form ever follows function” and 136 years before Ludwig Mies van der Rohe said “less is more,” to a newspaper interviewer. Unlike these giants, however, the Shakers also valued simplicity as a spiritual aid, believing the “superfluously wrought . . . would have a tendency to feed the pride and vanity of man.” Surrounded as they were during the 19th century with some truly horrendous worldly ornamentation, it probably would not have occurred to the Shakers that something like minimalism could be a source of vanity.

The Shaker notion that simplicity is a gift from God, that work is a religious exercise has never been encouraged by The World. The oldest and most successful of the early American utopian communities, they have not been alone in requiring celibacy, pacificism and communal property, but for most of their existence they have been unusual among Utopian groups in valuing gender and racial equality. They have lived, worked and worshipped in communities apart from their non-Shaker neighbors in order to prevent individual persecution as well as to avoid the influence of a sinful world. They settled in 18 self-contained communities from Maine to Kentucky, but while they were out of this world, they were also very much in it.

If it was cheaper to buy something from the outside world than to make it themselves, they bought it—pigment for those wild paints, the porcelain knobs that are often considered a Shaker signature, metals, glass, ceramics, bricks, sugar, vinegar, specialized machinery to prepare large quantities of food, and packaging materials (including firkins, or small kegs).

The contents were Shaker, but it was more efficient to purchase glass jars and bottles from the outside world. Image: Bard Graduate Center

Since they were already mass producing things like chairs, brooms, pails, storage boxes, cheese, dried sweet corn for themselves, they began selling to the outside to earn income for the community. The Shakers sold pulpwood and agricultural products, and are thought to be the first to market small, consumer-sized packets of garden seeds. They sold catsup, milk, cream, butter, lemon syrup for both lemonade and medicinal use, canned vegetables, baked beans, pickles, mincemeat, honey, tins of culinary herbs, and all manner of candy: hand-dipped chocolates, taffy, maple-sugar cakes, ribbon candy, fudge.

If a Shaker community had a resident printer, the labels were likely to be made on site. Other communities had the printing done by outsiders

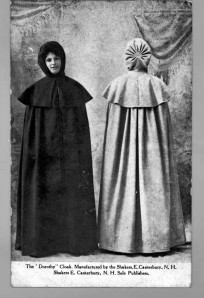

“Intellectually we don’t think of the Shakers as commercial people, but they were very entrepreneurial,” according to Jean Burks. They took orders for opera cloaks called “Dorothy Cloaks,” named after the Eldress at Canterbury Village in New Hampshire who designed them. The hooded cloaks were made of richly colored imported French wool, silk-lined and tied under the chin with a wide silk ribbon. The cloaks sold from $10 to $30 at a time when a skilled worker made $1 or $2 a day; in 1893, Grover Cleveland’s wife wore one to his inauguration.

The Dorothy Cloak, named after the Shaker sister who designed it, was made of French wool in rich colors and lined in silk.

The Shakers provided merchants with point-of-sale materials like posters for store windows, and sold applesauce, cider and dried apples to wholesale accounts. The headings on their price lists and invoices read “United Society,” not Shaker, originally a derogatory name based on the ecstatic nature of their worship, a name with which it took them a long time to come to terms. But as “Shaker” became an indicator of quality, ingenuity and value, they traded on it for all it was worth.

Large advertising poster for vegetable seeds sold by the MountLebanon, NY, Shakers.

They trademarked the logo that they attached to every chair they made, and because of their reputation for quality and purity, did a thriving business in remedies and medicinal herbs: toothache pellets, 221 herbs available in 300 forms, an asthma formula. They also understood the value of what we call “curb appeal,” positioning their most impressive, lightest colored buildings close to public roads or on high elevations where they could operate as advertisements for the Shaker way of life.

As the Shakers developed a reputation for excellence, they became adept at branding. They produced their wildly popular chairs n assembly-line fashion.

They also made and sold to the outside world items that were not simple enough for their own use: a preparation to darken gray hair, fancy pincushions including “screwballs” that clamp onto sewing tables, fans made of white turkey feathers, dolls dressed in little Dorothy Cloaks. Poplar keepsake boxes were such big sellers that before school each morning, every girl was required to weave at least one yard of cloth made of cotton thread and poplar shavings—the wood not being useful for furniture or fuel.

Left & center: Fancy velvet-covered standing pincushions made by Shakers for sale to the outside world. The “screwball” at right attaches to a table.

Doll wearing “Dorothy Cloak” was sold to the outside world.

They peddled souvenirs to resort hotels and vacation spots from Maine to Florida, and even developed mail order businesses. Twice a week, Sisters from the Sabbathday Lake community in Maine sold their goods in the lobby of the Poland Springs Resort Hotel (yes,that Poland Springs).

The Shakers were often adept photographers. In 1910, Brother Delmer C. Wilson took this shot of the Poland Spring Hotel, where Shaker Sisters set up shop in the lobby.

According to Jean Burks, the Shakers tended to have electricity and plumbing before their worldly neighbors did. In 1909, they became the first people in New Glouster, Maine, to buy a car; it cost $2,100. The Cleveland Plain Dealer reported that some Ohio Shakers “proposed to buy an aeroplane from the Wright brothers and operate it for their own pleasure.” No corroborating evidence has been found, but Michael Graham, curator at the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Museum in New Glouster, ME, says the Shakers have always been “on the cutting edge of technology.” The surviving Quakers, who conduct a business in the herbal teas, potpourri, cooking spices and balsam pillows that they still make at Sabbathday Lake (http://www.shaker.lib.me.us/catalog.html), could not keep going without their computers and microwaves.

In order to simplify their lives and streamline their work, the Shakers embraced new technologies and when those didn’t satisfy their needs, invented their own: the flat broom, the metal nib pen, a machine for making tongue-and-groove boards and permanent press, stain-resistant fabric using heat, pressure and zinc chloride to cut down on laundry chores. The circular saw was invented by a Sister Tabitha Babbitt of the Harvard, MA, Shakers, who was inspired by her spinning wheel. After watching two men struggle to cut timber with a pit saw, she attached a notched tin disk to her spinning wheel, pushed a piece of wood into it and changed the lumber industry worldwide.

Although they preferred to share their inventions with the world, the Shakers have been credited with over 100 patents, 37 of which have been verified, including 1852’s patent #8771 for a button-joint tilter, a small, commonsensible addition to the back legs of chairs to allow sitters to tilt back without slipping, damaging floors or stressing chair components.

The Shaker-patented tilters on the back legs of this chair made it possible to lean back without damaging the chair or the floor. Image: Bard Graduate Center

They also invented and patented a commercial washing machine and, in 1876, a commercial oven featuring revolving metal shelves pierced to allow even heating, isinglass (transparent, temperature-resistant mica) windows, and a temperature gauge—a great rarity at the time. The oven could bake 60 pies or 70 loaves of bread at one time, and was purchased by bakeries in the outside world.

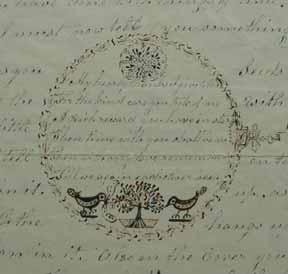

One thing they did not sell—or even display—were the “gift” drawings and paintings we’ve come to think of as prints to hang on a wall. These are really reports of dreams, visions and messages of love and encouragement. Some came from Mother Ann and other deceased elders, some from Indians, Blacks, Persians, Jews and Chinese sources, and some from such notables as George Washington, Christopher Columbus, William Penn, Napoleon, Mahomet, Pope Leo X, St. Patrick, and Alexander Pope. Some “gifts” are indescipherable, while others contain recognizable flowers, moons, stars, hearts, angels, houses, mills and even wheels and pulleys, indicating that the Shakers seemed to think there might be machinery in heaven.

Gift drawings were messages of love and encouragement, and never meant as wall decor.

5 Responses

Subscribe to comments with RSS.

I can hardly believe that Shaker’s had colorful furniture.

A lot of surprises here. I always thought of the Shakers as being somewhat monastic, but apparently they were very involved, actually in the forefront, of new ideas and technologies. Very different from the Amish who I thought they were similar to culturally.

Fascinating, well-written, informative. I had no idea the Shakers were so ahead of their time and creative in so many ways. Thanks for sharing this via nwu.

Nicely done. Have you published this as an article somewhere? Shook up my inadequate knowledge of the Shakers and their contributions to society.

Shaker color! Who knew. Thanks for enlightening me. Excellent article and illustrations. This is so like what has happened with Greek and Roman sculpture, which apparently were often or always colored originally. Was there a news peg for this? Wish I had seen the Bard exhibit.